Seung Yul Oh | Bod

02.28 - 03.28

Seung Yul Oh’s playful, crossmedia practice merges East Asian popular culture with wry references to Western art history. Born in Seoul, Korea in 1981 and later trained at Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts, he works across sculpture, installation, painting, video, performance, and largescale public commissions.

Oh’s works are instantly recognisable for their whimsical manipulation of scale, surfaces, and participatory or immersive qualities, ranging from inflated PVC environments to monumental public sculptures. Every work reimagines the ordinary and familiar with a mixture of humour, precision, and conceptual sharpness.

The paintings in Bod reject the established niceties of painting as either a perspectival space or flat surface for something much more malleable. Tracing the lineaments of experience: memory and forgetting, distance and absence – the artist defies the rules of and traditions of paintings. The centre cannot hold and is empty. The action takes place around the edges where experience warps, refracts and kaleidoscopically folds in on itself, hinting at infinite recursion.

As is often the case, the most interesting stuff is happening in the margins excluded from the centre. That is something directly informed by the immigrant experience, shifting between codes and orbits, never quite being allowed to land. Everything is a negotiation. The immigrant is, by default, like Schrödinger’s Cat, in multiple states simultaneously only to take form and be defined by whomever is looking. The painting becomes a manifestation of Homi Bhabha’s “third space” where new meanings are negotiated between cultures.

In a way this evokes Bruno Latour’s notion of iconoclash, the moment when an image, object, or representation is attacked, defended, or transformed in ways that make it impossible to tell whether the act is destructive, creative, or something in between. Instead of the clean moral drama of the “iconoclast” smashing false idols, Latour argues that modernity is full of ambiguous encounters where images are simultaneously revered, critiqued, dismantled, and remade.

Iconoclash is a zone of uncertainty: the hammer raised against an image might be an act of purification, a gesture of devotion, a bid for political power, or a creative reconfiguration of meaning. Latour’s point is that we cannot assume we know what images do, or what people do to images, until we trace the networks of intention, interpretation, and material practice that surround them. To an extent that is also part of the diasporic experience, to simultaneously unsettle, adapt, renew and perhaps even improve themselves and their new situation.

The sculptural component of Bod is similarly concerned with insides and outsides, function and form. With the work Bod, which gives the show its name – “body” but not quite – disposable food containers, with all of their ephemeral, disposal and ethnic resonances, are transformed into what the artist calls a “figure of embodiment” rather than a “vessel of use”. Function is purged yet the formal qualities remain.

Updating the objet trouvé and Duchampian readymade, the containers in this installation occupy space as a “standardized body already inscribed by systems of measurement and control.” Indeed, they are defined by these systems, much as human beings are defined by social expectations and economic expectations.

Each unit repeats across the room like a field of bodies in a stadium or square, their identities predetermined prior to any action. In Oh’s words “recalling both the disciplinary production of the subject and the phenomenological sense of the body as a given limit.” There is a mass, totalitarian terror in that, an obedient parade for a Benthamian panopticon. This kind of mass political aesthetic is familiar to us from George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four, from the Nuremberg Rallies, from every time Dear Leader appears before the North Korean crowds, and very likely from our own corporate capitalist existence.

But then, perhaps, the human body may only be another kind of container to keep memes, emotions, received aesthetics and ideologies in. Are we, as Milan Kundera implies, merely hosts for contagious, assimilating, homogenising mannerisms? Biologically we are not one conscious entity either, but a seething community of cells and microorganisms. We are infinitely mutable and adaptable.

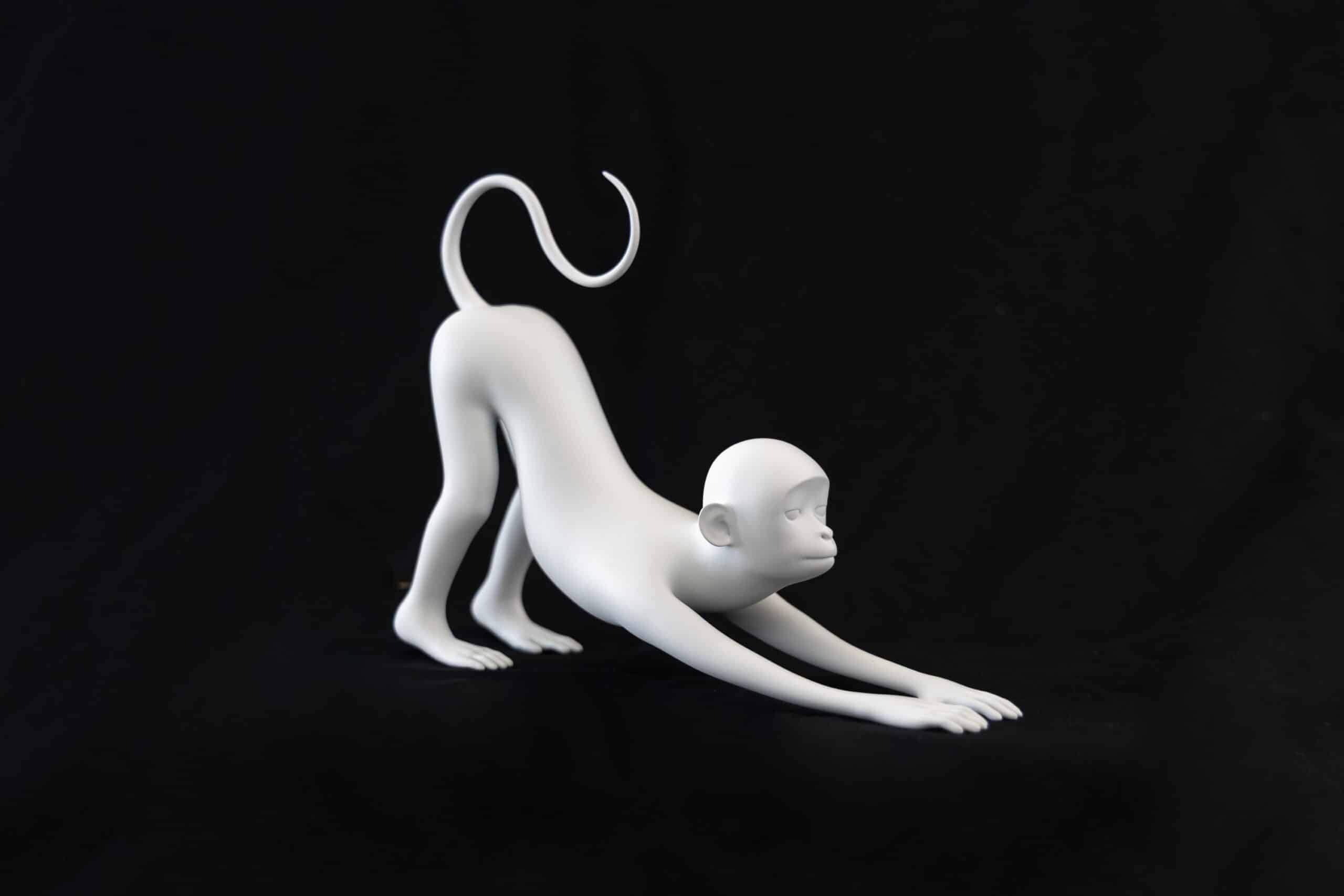

In contrast, the sculptural work Pre stages a body still in the realm of potentiality. On one level it is simply a delightful piece of Jeff Koons-esque (through an East Asian lens) pop art, a stylised monkey posed like the “downward dog” yoga position. “Pre” implies the conceptual experience prior to an event. The monkey is neither one thing nor the other, unresolved, an Ur-state tabula rasa. There is a temptation to project our own desires, fantasies and interpretations upon it.

In Pre we see the manifestation of potential, the divergent point of all possible universes. Is the monkey preparing to leap or is it stretching before it raises itself upright? The monkey is between human and animal, suspended before an observed even defines it. Weirdly it is as if Shrödinger’s box, unopened, has become transparent, but before the waveform has collapsed, before the fog of quantum uncertainty has cleared.

Together, Bod and Pre describe, as Oh puts it, “a tension between bodies shaped by external regimes and bodies that remain in the open, pre-formal state of becoming.” They are immanent – which is to say, they exist in a way where meaning, force or being arise entirely from within a given field, whether that be life, matter, language, society, or whatever – without an appeal to an external, transcendent source – the divine, Nature. Platonic forms or the abstract “Human” essence.

Gilles Deleuze embraced the concept of immanence this fully: for him, a plane of immanence is the self-organising, self-differentiating field in which all events occur, a world without outside, where difference is productive and affirmative. For the food containers there is only that collectively self-defined plane of immanence, but frozen in ataraxia, incapable of becoming. That does not preclude a whole universe inside each of them, however. We can only see the surface we are allowed to see.

Jacques Derrida took a different view, arguing that such purity is structurally impossible: any supposed immanent field is always already breached by différance, the play of traces that prevents full presence, self-coincidence, or closure. Derrida deconstructs the very idea of Deleuzian purity, showing that immanence cannot be pure because every “inside” depends on what it excludes, defers, or cannot contain. This is the approach encapsulated in Pre and the paintings – self-contained but open, imbued with différance.

In sum, the interplay between Bod and Pre and the paintings invites us to reconsider how bodies, sculptural, social, or conceptual, are shaped, defined, and suspended between states of being. The works evoke both the discipline of external systems and the openness of potentiality, challenging us to question the boundaries of identity, function, and meaning. Ultimately, they suggest that the process of becoming is never fully closed, always marked by uncertainty, negotiation, and the possibility of transformational becoming.